The incidence of colony mortality is far greater in the winter than at any other time. This is generally due to the bees being confined to their hive for long periods, and any problem, such as disease, queen failure or depletion of stores, cannot easily be rectified. The beekeeper is unable to detect any winter problems within the hive, as the weather is usually too bad to risk opening up and disturbing the winter cluster. Careful preparation for winter therefore, is vital to both bees and beekeeper. The potential problems are worthy of closer scrutiny, as preparations are made in September.

Disease

If the colony has been disease free through the summer, then there should be little to worry about as they go into winter. There are however, some precautions worth taking.

Strange though it may seem, the bees' own honey is not always the best food to see them through the winter. Some honeys, such as heather and honeydew, are high in fibre, and if this is the only food available, it results in the bees need to defecate more frequently. If the winter weather prevents cleansing flights, then dysentery occurs on the combs, and will spread quickly through the colony. It is therefore beneficial for the bees to be fed at least some sugar syrup, in order to ensure that their winter stores will not harm them.

Strange though it may seem, the bees' own honey is not always the best food to see them through the winter. Some honeys, such as heather and honeydew, are high in fibre, and if this is the only food available, it results in the bees need to defecate more frequently. If the winter weather prevents cleansing flights, then dysentery occurs on the combs, and will spread quickly through the colony. It is therefore beneficial for the bees to be fed at least some sugar syrup, in order to ensure that their winter stores will not harm them.

Queen Failure

This usually occurs in an ageing queen, so the remedy is simple. Make sure that the over-wintering colony is headed by a queen not more than three years old, preferably two. Other problems can include queens who are not mated well, or which have suffered some kind of physical damage, but these would typically cause supersedure of the queen in the autumn.

Pests, Predators and Parasites

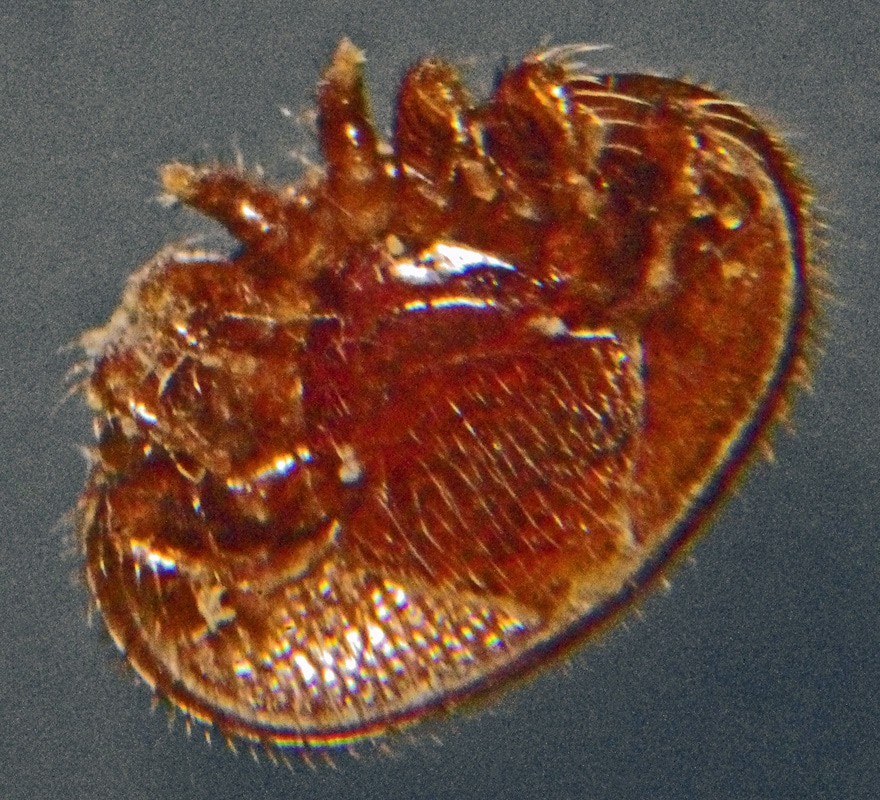

This is another area where the beekeeper’s winter preparations are vital to the bees. The honeybees’ principal parasite is the Varroa mite, and without man’s intervention, they would succumb to this infestation. Complete eradication of the mite is unfortunately, not an option, so several management techniques have been developed to reduce the over all number in the hive. These include Queen Trapping, Drone Culling, the use of Icing Sugar or Talcum Powder, Open Mesh Floors, and Alternating Treatments. By integrating some of these management techniques, Varroa control is not difficult. Details of all these techniques can be obtained from the National Bee Unit, but let us concentrate here on the simple basic operations, which take the minimum of time, and have the desired effect.

It is claimed that twenty to twenty five per cent of Varroa mites, at some stage, lose their foothold and drop to the floor. If a solid floor is being used, the mite simply hitches a lift on the next passing bee, and before you know it, it is back up among the cluster. If however, an Open Mesh Floor is used, these mites will drop through onto the ground below, and that’s twenty to twenty five per cent of the problem solved, and it takes the beekeeper no time at all. This type of control can be used both winter and summer. All Open Mesh Floors should include a tray, which can be slid in below the mesh, and which can be used to monitor natural mite drop. The tray is usually installed for a period of five days, after which the number of mites can be counted, and used to calculate the level of infestation within the hive. Another simple method of checking Varroa levels is to extract drone pupae from their cells using an uncapping fork. If the prongs of the fork are inserted just below the surface of the cells, a number of pupae can easily be removed for inspection. The reddish mites will show up very clearly against the white pupae.

Drone Culling is another method of removing a number of mites, and this can be done in conjunction with open mesh floors, and takes very little time. It is a recognised fact that Varroa mites prefer to reproduce in drone cells, because of the extended period in which the drone pupae develop. Therefore, if drone brood can be encouraged for a short period, the mites will be encouraged to migrate into these drone cells, and when capped, the brood can be sacrificed along with a substantial number of Varroa mites. This can best be achieved in the spring, when the bees are anxious to produce drones for the coming season. By placing two shallow frames of worker comb in the brood chamber, the bees will be induced to draw wild comb below the bottom bars, to fill up the excess space. In spring, this comb will most likely be drone comb, and will attract Varroa mites. When the cells are capped, the frames can be removed, and the wild drone comb cut off and destroyed. The frames, which now contain only worker brood, can then be returned to the brood chamber, where the operation can be repeated until the wild comb is eventually drawn down as worker comb. At this point, the frames should be worked, in stages, first to the edge of the brood nest, where the worker brood is allowed to emerge, and then to the outer edge of the brood chamber, where they can be replaced with normal brood frames. Two points worthy of mention here are that the two shallow frames should not be placed in consecutive positions, as the space created below could result in uncontrolled wild comb being produced. The frames should be placed in the centre of the brood nest, either side of a normal brood frame. Secondly, care must be taken not to allow the resulting drone brood to emerge, for if that were to happen, we would be breeding mites, not controlling them.

As we approach the end of the summer, the bees, in preparation for the coming winter, are reducing the brood area. Because the number of cells in which the mites can hide is now greatly diminished, it is a good time to consider treatment.

It should be emphasised that any honey, intended for human consumption, should be removed before treatments are applied as, with one exception, they will taint the honey. The exception is MAQS (mite away quick strips) which are placed on the hive for only seven days, and will not taint the honey. You have to be careful not to treat when the weather is hot, as the bees will react and are known to vacate the hive, preferring to cling to the outside. Some beekeepers report losing queens when using MAQS.

Initially, when Varroa was first discovered in the UK, the only treatment licensed was Bayvarol, a pyrethroid based treatment. After a few years, this was joined by Apistan, but this was a similar product with a similar base. Within ten years, Varroa had developed a resistance to pyrethroid-based treatments. An alternative treatment was required. For several years, Vita (Europe) Ltd had been developing a thymol-based product called Apiguard. This was granted a licence and became a legitimate alternative; indeed with pyrethroid resistant mites common in most areas of the UK, non-pyrethroid treatments are often the only solution. Similar treatments to Apiguard such as Api Life Var are now also approved. However an increasing number of beekeepers are now using treatments based on the use of oxalic acid, applied either through trickling or vaporisation; the advantage of both of these techniques is that they are applied in winter, when there is very little brood, and therefore the treatment can be extremely effective.

Apigaurd and Api Life Var are applied in similar ways.

Apiguard is a thymol-based gel, which functions in two ways. The slow release gel evaporates, producing a vapour, which is heavier than air, therefore open mesh floors should have their trays in place, or the hive placed on a solid floor for the period of the treatment. The second way in which the treatment works is by the bees physically removing the gel, and carrying it down between the frames effecting further dispersal. Of course, in order to do this, they must have access to the trays in which the gel is applied. The trays are placed immediately on the top bars of the brood chamber, immediately following removal of the honey crop. First one is put in place, then two weeks later another joins it, and the two are left in position for a further four weeks, making a six week treatment in all. In order for the bees to have physical access however, the trays require housing, for if the crownboard is placed immediately back on the brood chamber, it will effectively seal off the tops of the trays. This housing is usually effected by the use of a two inch eke, and then the crownboard placed on that. Because thymol relies upon evaporation, the treatment is temperature sensitive, requiring a minimum of 15c; therefore treatment must begin in August, as soon as the honey crop has been removed. If it waits until September, the ambient temperature towards the end of the treatment period might render it less effective.

Api Life Var is also based on essential oils, including thymol, but the application is slightly easier, as it does not require an eke. The 'bars' of Api Life Var are simply broken into four pieces, and placed on top of the brood frames in the corner of the hive. As with Apiguard, the ambient temperature is important in order to evaporate the essential oils.

If a pyrethroid based product (Bayvarol or Apistan) is being used, this is even easier to apply. These are contact treatments, relying upon the bees crawling over them. Both brands take the form of impregnated strips, which are hung down between the brood frames, and left for a period of six weeks. Because the treatment does not rely on evaporation, it can be applied in September, bearing in mind that the later it is applied, the further into winter it will be when removal is necessary.

The correct method of applying oxalic acid is the subject of many articles and debates, and before products such as Api-Bioxal were licensed, it was difficult to judge the correct quantities to use in order to maximise effectiveness against varroa without damaging the bees. However, the essentials are as follows, and both trickling and vaporisation work best when there is little or no brood, i.e. in the depths of winter.

Included among the pests and predators that can be a problem in the winter, are mice, green woodpeckers, deer and badgers. Of these, mice are probably the most prevalent. During the active season, a mouse wouldn’t dare set foot inside the hive entrance, but in the winter, when the bees are tightly clustered; it is very easy for one to creep in without detection. A beehive is ideal winter quarters. It is warm, dry, and has a built in food supply. Once inside, the mice usually make a nest, which means the destruction of combs and frames. The remedy is simple however. A mouse guard placed across the entrance, and secured with drawing pins or clips, will keep the mice at bay.

Green woodpeckers are usually only a problem in a very hard winter. If the ground becomes frozen for long periods, preventing them from getting to their normal food source, ants, they will sometimes attack beehives, drilling their way through the side of the brood chamber, and completely ruining it. The answer to this problem is chicken wire wrapped around the hive.

Badgers, again, are not usually a problem. They will sometimes scratch at the hive entrance, dislodging the mouse guard, and they will sometimes put their front paws on top of the hive in an effort to push it over, but if the hive is on a firm support, they will not succeed. A good heavy stone on the roof will help to keep it stable. Better still, stand the hive on a concrete slab, and place a ratchet strap underneath it, allowing you to strap the hive down over winter.

Finally, there is the weather to consider. Cold doesn’t kill bees, damp does. Ventilation is even more important in the winter than it is in the summer. Any entrance blocks should be removed before fitting mouse guards, and the entire entrance left open. This, together with open mesh floors will ensure adequate ventilation from the bottom of the hive. The feed holes in the crown board should be left open, and the ventilation outlets in the roof should be freed of any blockage. It is worth mentioning here, that the crown board should be a ply wood type, not glass, as glass will collect condensation, which will drip down onto the bees and could be fatal. In some exposed areas, the winter gales can sometimes blow snow or rain in through the entrance, so unless an open mesh floor is being used, a batten should be placed under the back of the hive, tipping it forward slightly, so that any water that finds its way in, can run out again.

It is claimed that twenty to twenty five per cent of Varroa mites, at some stage, lose their foothold and drop to the floor. If a solid floor is being used, the mite simply hitches a lift on the next passing bee, and before you know it, it is back up among the cluster. If however, an Open Mesh Floor is used, these mites will drop through onto the ground below, and that’s twenty to twenty five per cent of the problem solved, and it takes the beekeeper no time at all. This type of control can be used both winter and summer. All Open Mesh Floors should include a tray, which can be slid in below the mesh, and which can be used to monitor natural mite drop. The tray is usually installed for a period of five days, after which the number of mites can be counted, and used to calculate the level of infestation within the hive. Another simple method of checking Varroa levels is to extract drone pupae from their cells using an uncapping fork. If the prongs of the fork are inserted just below the surface of the cells, a number of pupae can easily be removed for inspection. The reddish mites will show up very clearly against the white pupae.

Drone Culling is another method of removing a number of mites, and this can be done in conjunction with open mesh floors, and takes very little time. It is a recognised fact that Varroa mites prefer to reproduce in drone cells, because of the extended period in which the drone pupae develop. Therefore, if drone brood can be encouraged for a short period, the mites will be encouraged to migrate into these drone cells, and when capped, the brood can be sacrificed along with a substantial number of Varroa mites. This can best be achieved in the spring, when the bees are anxious to produce drones for the coming season. By placing two shallow frames of worker comb in the brood chamber, the bees will be induced to draw wild comb below the bottom bars, to fill up the excess space. In spring, this comb will most likely be drone comb, and will attract Varroa mites. When the cells are capped, the frames can be removed, and the wild drone comb cut off and destroyed. The frames, which now contain only worker brood, can then be returned to the brood chamber, where the operation can be repeated until the wild comb is eventually drawn down as worker comb. At this point, the frames should be worked, in stages, first to the edge of the brood nest, where the worker brood is allowed to emerge, and then to the outer edge of the brood chamber, where they can be replaced with normal brood frames. Two points worthy of mention here are that the two shallow frames should not be placed in consecutive positions, as the space created below could result in uncontrolled wild comb being produced. The frames should be placed in the centre of the brood nest, either side of a normal brood frame. Secondly, care must be taken not to allow the resulting drone brood to emerge, for if that were to happen, we would be breeding mites, not controlling them.

As we approach the end of the summer, the bees, in preparation for the coming winter, are reducing the brood area. Because the number of cells in which the mites can hide is now greatly diminished, it is a good time to consider treatment.

It should be emphasised that any honey, intended for human consumption, should be removed before treatments are applied as, with one exception, they will taint the honey. The exception is MAQS (mite away quick strips) which are placed on the hive for only seven days, and will not taint the honey. You have to be careful not to treat when the weather is hot, as the bees will react and are known to vacate the hive, preferring to cling to the outside. Some beekeepers report losing queens when using MAQS.

Initially, when Varroa was first discovered in the UK, the only treatment licensed was Bayvarol, a pyrethroid based treatment. After a few years, this was joined by Apistan, but this was a similar product with a similar base. Within ten years, Varroa had developed a resistance to pyrethroid-based treatments. An alternative treatment was required. For several years, Vita (Europe) Ltd had been developing a thymol-based product called Apiguard. This was granted a licence and became a legitimate alternative; indeed with pyrethroid resistant mites common in most areas of the UK, non-pyrethroid treatments are often the only solution. Similar treatments to Apiguard such as Api Life Var are now also approved. However an increasing number of beekeepers are now using treatments based on the use of oxalic acid, applied either through trickling or vaporisation; the advantage of both of these techniques is that they are applied in winter, when there is very little brood, and therefore the treatment can be extremely effective.

Apigaurd and Api Life Var are applied in similar ways.

Apiguard is a thymol-based gel, which functions in two ways. The slow release gel evaporates, producing a vapour, which is heavier than air, therefore open mesh floors should have their trays in place, or the hive placed on a solid floor for the period of the treatment. The second way in which the treatment works is by the bees physically removing the gel, and carrying it down between the frames effecting further dispersal. Of course, in order to do this, they must have access to the trays in which the gel is applied. The trays are placed immediately on the top bars of the brood chamber, immediately following removal of the honey crop. First one is put in place, then two weeks later another joins it, and the two are left in position for a further four weeks, making a six week treatment in all. In order for the bees to have physical access however, the trays require housing, for if the crownboard is placed immediately back on the brood chamber, it will effectively seal off the tops of the trays. This housing is usually effected by the use of a two inch eke, and then the crownboard placed on that. Because thymol relies upon evaporation, the treatment is temperature sensitive, requiring a minimum of 15c; therefore treatment must begin in August, as soon as the honey crop has been removed. If it waits until September, the ambient temperature towards the end of the treatment period might render it less effective.

Api Life Var is also based on essential oils, including thymol, but the application is slightly easier, as it does not require an eke. The 'bars' of Api Life Var are simply broken into four pieces, and placed on top of the brood frames in the corner of the hive. As with Apiguard, the ambient temperature is important in order to evaporate the essential oils.

If a pyrethroid based product (Bayvarol or Apistan) is being used, this is even easier to apply. These are contact treatments, relying upon the bees crawling over them. Both brands take the form of impregnated strips, which are hung down between the brood frames, and left for a period of six weeks. Because the treatment does not rely on evaporation, it can be applied in September, bearing in mind that the later it is applied, the further into winter it will be when removal is necessary.

The correct method of applying oxalic acid is the subject of many articles and debates, and before products such as Api-Bioxal were licensed, it was difficult to judge the correct quantities to use in order to maximise effectiveness against varroa without damaging the bees. However, the essentials are as follows, and both trickling and vaporisation work best when there is little or no brood, i.e. in the depths of winter.

- Trickling - Oxalic acid in the correct concentration in a sugar syrup (4.2%) is trickled onto seams of clustering bees in between the frames. The bees then transfer the syrup around the hive, and it kills the varroa mites by contact.

- Vaporisation - Anhydrous oxalic acid is heated in a vaporiser (normally powered by a 9v battery), and as it vaporises, is distributed via a short tube into the hive. The oxalic acid then crystallises around the hive, and again kills varroa mites via contact.

Included among the pests and predators that can be a problem in the winter, are mice, green woodpeckers, deer and badgers. Of these, mice are probably the most prevalent. During the active season, a mouse wouldn’t dare set foot inside the hive entrance, but in the winter, when the bees are tightly clustered; it is very easy for one to creep in without detection. A beehive is ideal winter quarters. It is warm, dry, and has a built in food supply. Once inside, the mice usually make a nest, which means the destruction of combs and frames. The remedy is simple however. A mouse guard placed across the entrance, and secured with drawing pins or clips, will keep the mice at bay.

Green woodpeckers are usually only a problem in a very hard winter. If the ground becomes frozen for long periods, preventing them from getting to their normal food source, ants, they will sometimes attack beehives, drilling their way through the side of the brood chamber, and completely ruining it. The answer to this problem is chicken wire wrapped around the hive.

Badgers, again, are not usually a problem. They will sometimes scratch at the hive entrance, dislodging the mouse guard, and they will sometimes put their front paws on top of the hive in an effort to push it over, but if the hive is on a firm support, they will not succeed. A good heavy stone on the roof will help to keep it stable. Better still, stand the hive on a concrete slab, and place a ratchet strap underneath it, allowing you to strap the hive down over winter.

Finally, there is the weather to consider. Cold doesn’t kill bees, damp does. Ventilation is even more important in the winter than it is in the summer. Any entrance blocks should be removed before fitting mouse guards, and the entire entrance left open. This, together with open mesh floors will ensure adequate ventilation from the bottom of the hive. The feed holes in the crown board should be left open, and the ventilation outlets in the roof should be freed of any blockage. It is worth mentioning here, that the crown board should be a ply wood type, not glass, as glass will collect condensation, which will drip down onto the bees and could be fatal. In some exposed areas, the winter gales can sometimes blow snow or rain in through the entrance, so unless an open mesh floor is being used, a batten should be placed under the back of the hive, tipping it forward slightly, so that any water that finds its way in, can run out again.