|

At this time of year, Asian Hornet primary nests are building up in size, and the amount of workers will be rapidly increasing, says our AHAT co-ordinator Lynne Ingram.

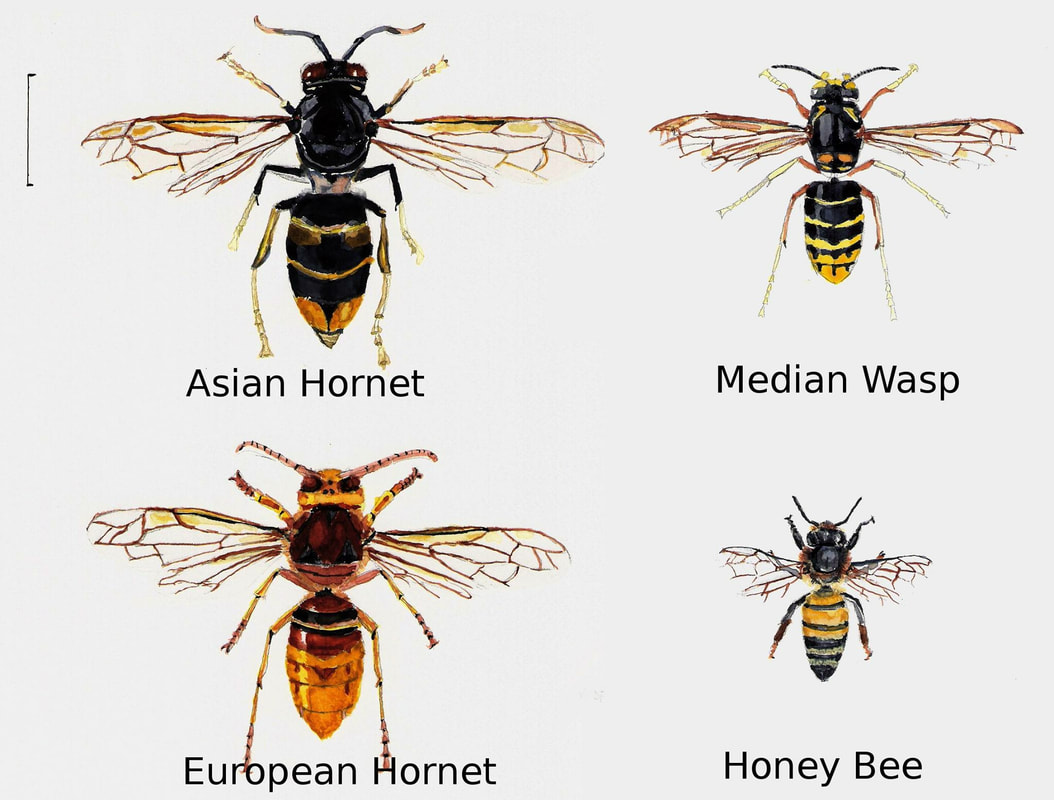

Primary nests are generally in sheltered low level places – maybe in a shed, a low bush, hedge or in a bramble patch. As the nest increases in size, the colony may outgrow this location, and 70 per cent of them will relocate to a secondary nest that they develop in a much higher and inaccessible position – often in a tree. For about a month, the two nests will continue to function in parallel until the larvae in the primary nest have all emerged. As we move towards mid to end of summer, the number of workers in the nests increases hugely and they will start to become more visible if they are in your area. Keep your eyes peeled for the sight of an Asian hornet in your garden or around your bee hives. Continue to monitor any traps in your garden or apiary. If you think you have spotted an Asian Hornet then take a photo so that we have some evidence of it. If you are sure, then report it through the Asian Hornet Watch app. If you are not sure, or need help identifying an insect or getting a photo, then contact your local Asian Hornet Team Coordinator or email: [email protected] Asian Hornet Watch app for iPhone Asian Hornet Watch app for Android SBKA’s Chair Stewart Gould writes in July’s newsletter that beekeeping is experiencing its own ‘impending pandemic virus’:

“CBPV has been with us for a while now, and is even mentioned in Ted Hooper’s Guide to Bees and Honey. My copy was published in 2008, and has a whole page on the subject of Chronic Bee Paralysis Virus. What differs between opinion in 2008 and the present day is that we no longer think of CBPV as being associated with acarine, and it can certainly be more virulent and deadly than as described by Ted Hooper. ‘With this type of paralysis the colonies are often very little affected and seem to be able to breed fast enough to keep the population up. From the literature, however, it is clear that many cases have occurred where colonies with paralysis have dwindled badly or died out entirely’. There has been a considerable upsurge in the number of cases in the last 2 or 3 years, with many experienced beekeepers reporting that they have only come across it in that time period. It can’t really be blamed on acarine anymore, as the treatments (miticides) which we use to attack varroa will also knock out acarine, as they are both mites. There are two distinct forms of CBPV, in type one, bees are found crawling outside the hive, on nearby plants, and have bloated, elongated abdomens with partially spread or dislocated wings. It can be serious with the colony succumbing completely, but what Ted Hooper didn’t do was separate out the two forms of the disease. Type two CBPV is, in the early stages, spotted when black greasy looking bees are spotted on the frames, and it can stop right there, but if it progresses, which it seems to be doing increasingly, bees will be seen trembling on the top bars of frames. If that wasn’t enough to grab your attention, the black greasy bees, as seen in the photo, which appear to be smaller because they are virtually hairless, will also be present, and you may soon notice bees trembling on the landing board, if you have one, or around the entrance, as in this video click here. Other bees will nibble at them, as if removing the hairs. Perhaps the most disconcerting evidence is a large pile of dead bees which may well appear immediately beneath the entrance. There could be hundreds and hundreds. Where did CBPV come from? It’s been here a good while, but present thinking is that it has been exacerbated by the increase of imported queens. There are varying reports on how much it affects the queens, but it is most obvious in adult workers, possibly because there are more of them than anything else, and the brood doesn’t seem to be affected at all. Bees are social insects, and when out and about, will greet each other by touching antennae, or make contact with their proboscises. Any virus would easily be transmitted from one to the other. Like Covid 19, we have no treatment for CBPV, as anything strong enough to kill the virus, would kill the bee – at present. We all know a littler bit more about viruses these days, and the best advice so far, is to wash your hands, because soap and water can break down the outer coating of the virus. The same applies to CBPV. Practising a healthy regime in your apiaries should help to contain any outbreak you may have. Changing hive tools between hives when inspecting, and washing both the hive tool and your gloves in a washing soda solution, will minimise the risk of introduction or transmission. It’s not all doom and gloom, some colonies do recover from CBPV. Of the six current cases I know, 3 hives have recovered, but please be mindful and keep a weather eye on your hives. CBPV can exist at a low ebb and just bumble along without becoming a major problem (asymptomatic) – in that hive, but it can easily be passed on to other colonies, and other beekeepers’ apiaries. It’s perhaps a little late now, but swarms can easily transmit the problem over miles at a time. Swarms have been extremely plentiful this year, but I hope you have managed to contain them, and following the reported bumper Spring crops, can look forward to an excellent main crop.” |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

Somerset Beekeepers Association Charity © 2021 Registered CIO Charity 1206483

Affiliated to the British Beekeepers Association

Click here to view our Privacy Policy

Affiliated to the British Beekeepers Association

Click here to view our Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed